Every one who dreams of calling himself a computer scientist ought to know a few things in his chosen profession. Regular expressions happen to be one of them, they appear deceptively simple when seen from the end of a good text editor, but if you went behind the curtains you’d find an intricate dance of some of the core concepts of computer science.

This blog is merely a pale shadow of this one. All of the concepts I shall talk about come from here and you are probably better off reading it, unless you don’t like scala. I originally implemented this project in scala too, but a few months later when I looked at my code it seemed to closely resemble gibberish, because I had forgotten how case classes work in scala, so I reimplemented it in python.

Scope

This project aims to implement the compile and matches functions. compile takes as input a regular expression, while matches inputs the string which is to be tested and informs if it matches the given regular expression.

I shall not be implementing all the features of a regular expression, because I am for the present only interested in understanding how it works. So it is sufficient to implement:

- One binary operator such as

| +to match one or more of the previous pattern*to match zero or more of the previous pattern

A bird’s eye view

Before we tackle each part of the regex in detail here is a quick overview of what is involved.

The compile method does four things:

- Analyzes the regular expression and puts in a special marker to understand which parts are going to be concatenated

- Takes the above input and converts it to a post fix expression

- Takes the above post fixed expression and converts it to an Abstract Syntax Tree(AST)

- Converts the AST to a Nondeterministic Finite Automata(NFA)

The matches method takes in the string to test and runs it through the NFA to see if it can reach the matching state.

Why NFA

The last time I dealt with NFAs was in my finite automata class where I labored over converting from DFA to NFA and figuring out if a certain input string matched a given NFA while I longed to get back to what I called the real world of computer science i.e. algorithms. When the class ended I did not stop to give finite automatas a second thought and moved on with coding. It took this excellent post by Russ Cox to enlighten me on how simple it is to re-imagine a regular expression as an NFA.

A simple example will suffice, say we have the following regular expression: ab*c+ The strings that will match this are ac, acc, abc, abbc etc.

This is what the NFA for this will look like:

We can see that all the example strings given above will lead to the matching state, while a string such as ‘ab’ will leave the NFA stuck in the S1 state.

Constructing an NFA

The path from an input regular expression string to an NFA contains an intermediate representation called an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) or parse tree. Here is what the AST would look like for ab*c+

The tree is a desirable data structure because as we’ll see below it is quite easy to convert from the regular expression string to a post fix expression with a well defined hierarchy. Traversing this tree is much simpler than traversing a string.

Given below are some of the prerequisites for forming the AST.

Detecting concatenation

We need a way to tell when two literals are going to be concatenated.

Why?

If you look at the NFA for ab*c+, zero or more ‘b’s need to be concatenated with one ‘a’, which needs to be concatenated with one or more ‘c’s. In order to create an AST from this string (i.e. ab*c+) we need to know when to concat.

This is accomplished by evaluating the input string one character at a time and keeping track of the last time we encountered a literal and the last time we encountered an operation. This is done by the append_concat function given below which inserts an extra ` when it decides a concatenation needs to be performed.

def append_concat_recursive(self, input, result, num_operands, prev_operator=None):

"""

Recursive function that decides where to put the . operator for concat

:param input: at each recursive call the input size reduces by input[1:]

:param result: at each recursive call result size increases by result += input[0]

:param num_operands: number of operators seen so far, if equal to 1 then . will never be placed

:param prev_operator: is prev_operator was a binary operator then . won't be placed

:return:

"""

if len(input) == 0:

return result

temp_result = result + input[0]

head_is_operator = input[0] in self.operators

head_is_bi_operator = input[0] in self.binaryOperator

head_is_parenthesis = input[0] in self.parenthesis

prev_operator_was_bi = prev_operator in self.binaryOperator

if input[0].isalnum():

num_operands += 1

if num_operands > 1 and not head_is_bi_operator and head_is_operator and not head_is_parenthesis \

and not prev_operator_was_bi:

temp_result += '`'

if head_is_operator:

prev_operator = input[0]

return self.append_concat_recursive(input[1:], temp_result, num_operands, prev_operator)

def append_concat(self, input, result):

"""

A landing function to call append_concat_recursive and set num_operands to 1 if needed

:param input:

:param result:

:return:

"""

num_operands = 0

if result.isalnum():

num_operands += 1

return self.append_concat_recursive(input, result, num_operands)

So an expression such as ab*c+ becomes ab*`c+` while an expression such as

a*|b+ remains unchanged since there is no concatenation.

Binding rules

Similar to the PEMDAS rule in arithmetic which can be implemented by converting to a post fix expression, there are a set of rules for evaluating regular expressions.

The point of a post fix expression is to define the importance of an operation, so for example in the expression

8 + 6 / 3 * 2

we have to evaluate the / first followed by a * and then +.

So the post fix expression for it will become:

8 6 3 / 2 * +

The binding rules for a regular expression are as follows (weaker to stronger):

- Literals and parenthesis

+and*- Concatenation

|defining the OR operation

This can be implemented quite easily with a infix to postfix converter with slightly modified rules for detecting precedence.

Constructing the AST

The main parts of the tree are:

- LITERAL

- OR

- CONCAT

- REPEAT

- PLUS

They can be implemented in any way, I chose to create classes for each of these which have nothing more than a constructor and all derive from one abstract parent class. The advantage of using classes is that my code becomes very easy to read.

class AST:

pass

class Literal(AST):

def __init__(self, lit):

self.literal = lit

class Or(AST):

def __init__(self, left, right):

self.left = left

self.right = right

class Concat(AST):

def __init__(self, left, right):

self.left = left

self.right = right

class Repeat(AST):

def __init__(self, expr):

self.expr = expr

class Plus(AST):

def __init__(self, expr):

self.expr = expr

The act of constructing the tree is extremely simple. You need to maintain a stack, look at each input string one character at a time and decide what object to push into the stack.

For example if you encounter a `, pop the top two items in the stack and use them to create a Concat object and push it into the stack.

Here is the code:

def postfix_2_AST(self, postfix_input):

"""

Converts the input from post fix notation to an AST

:param postfix_input:

:return:

"""

AST = []

for ch in postfix_input:

if ch is '*':

expr = AST.pop()

AST.append(Repeat(expr))

elif ch is '+':

expr = AST.pop()

AST.append(Plus(expr))

elif ch is '`':

right = AST.pop()

left = AST.pop()

AST.append(Concat(left, right))

elif ch is '|':

right = AST.pop()

left = AST.pop()

AST.append(Or(left, right))

else:

AST.append(Literal(ch))

return AST.pop()

Constructing the NFA

There will be several discrete pieces that will go into building the NFA, here are the things that we need to handle:

- LITERAL

- OR

- CONCAT

- REPEAT

- PLUS

This list is identical to what we needed to handle for the AST. Each of the above states is modeled as having an Input state and an Output state which allow us to chain them together. First let’s put up the function that does the conversion to NFA. I’ll explain each case so don’t get too involved with the ‘if’ cases.

def AST_2_NFA(self, ast, and_then):

"""

Converts the AST to an NFA

:param ast: Current state

:param and_then: Next state

:return: A state object

"""

if isinstance(ast, Literal):

return Consume(ast.literal, and_then)

elif isinstance(ast, Concat):

return self.AST_2_NFA(ast.left, self.AST_2_NFA(ast.right, and_then))

elif isinstance(ast, Repeat):

placeholder = Placeholder(None)

split = Split(self.AST_2_NFA(ast.expr, placeholder), and_then)

placeholder.pointing_to = split

return placeholder

elif isinstance(ast, Or):

split = Split(self.AST_2_NFA(ast.left, and_then), self.AST_2_NFA(ast.right, and_then))

return split

elif isinstance(ast, Plus):

return self.AST_2_NFA(Concat(ast.expr, Repeat(ast.expr)), and_then)

else:

return Consume("", and_then)

The input parameter ‘ast’ points to the current state of the AST and ‘and_then’ points to the next state in the AST. When this method is invoked for the first time I pass in the Match object for the ‘and_then’

Now let’s look at each part individually.

Literals

Literals are modeled using the Consume class

class State:

pass

class Consume(State):

def __init__(self, to_consume, out):

self.to_consume = to_consume

self.out = out

class Match(State):

pass

State is an abstract class and out points to the next State that the NFA will be in once it has consumed the literal pointed to by the to_consume string.

For example if the regular expression was a, then to_consume would point to the character ‘a’ and out would point to the Match class

Or

This is modeled as a Split class.

class Split(State):

def __init__(self, out1, out2):

self.out1 = out1

self.out2 = out2

When we encounter an OR object of the AST, there will be a left and right object. Using these we can generate a Split object where out1 points to the AST’s left object and out2 points to the AST’s right object. This is what it’d look like

Concat

The Concat object of the AST also has left and right pointers.

When we reach a Concat object of the AST, we need to chain the left State object’s out to point to the right State object’s in, and the right state object’s out should point to the and_then state at the time of method invocation.

Here is what it’d look like

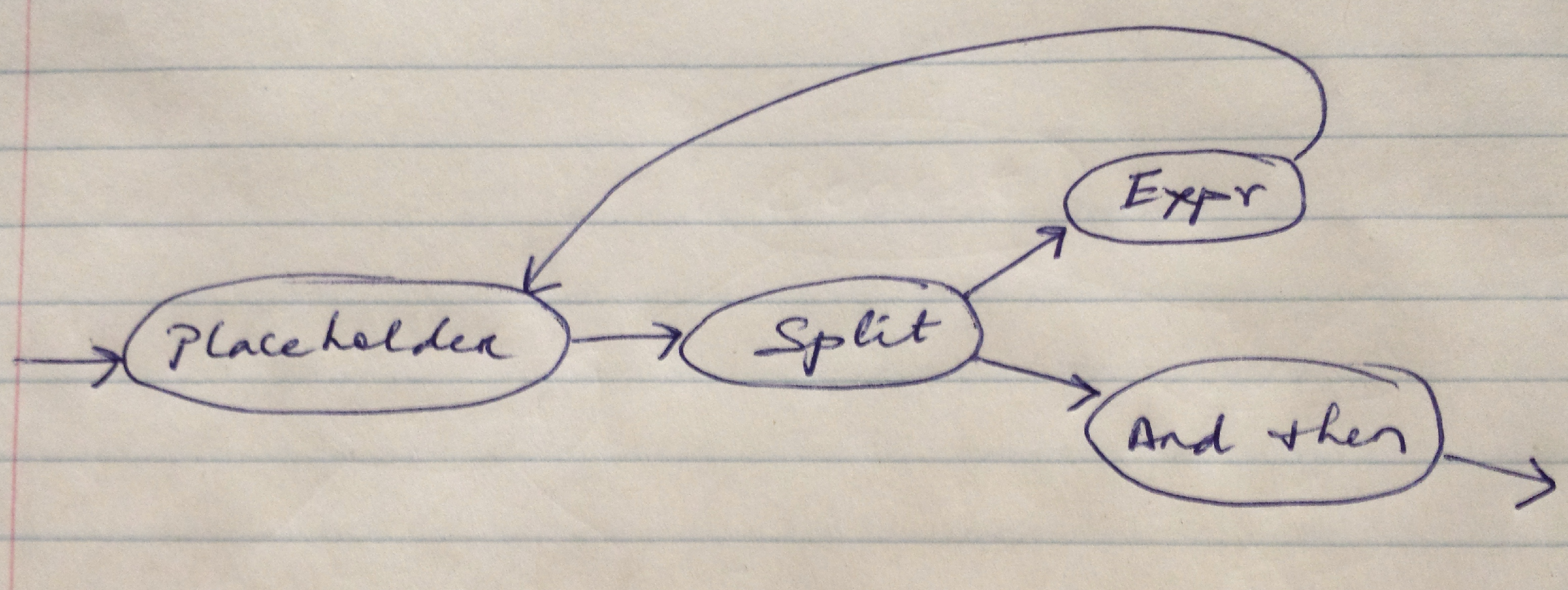

Repeat

This is the most complex bit of code here and bears extra explanation. The code looks as follows

if isinstance(ast, Repeat):

placeholder = Placeholder(None)

split = Split(self.AST_2_NFA(ast.expr, placeholder), and_then)

placeholder.pointing_to = split

return placeholder

Here is what it’d look like

First am empty placeholder object is created whose pointee is then set to the Split object. This creates an infinite loop chain which is what we need for *.

The Split object itself holds the requisite expression on the left side and the exit condition on the right side.

The placeholder object provides an easy way to set the loop.

Plus

This operation is composed by using two of the above states

Plus(Literal(X)) = Concat(Literal(X), Repeat(Literal(X))

This concludes the creation of the NFA, all that remains is

Traversing the NFA

This is a much simpler process which involves consuming the input string one character at a time and running through the NFA, if the string finishes before the reaching the Match state or it leads to a state that is not in the NFA we can return False.

Here is the code

def evaluate_NFA(self, curr_state, string_to_match):

"""

Runs the string_to_match on the NFA to see if it can reach the Match state

:param curr_state:

:param string_to_match:

:return:

"""

if isinstance(curr_state, Consume):

if len(string_to_match) == 0:

return False

if string_to_match[0] != curr_state.to_consume:

return False

return self.evaluate_NFA(curr_state.out, string_to_match[1:])

elif isinstance(curr_state, Placeholder):

return self.evaluate_NFA(curr_state.pointing_to, string_to_match)

elif isinstance(curr_state, Split):

lhs = self.evaluate_NFA(curr_state.out1, string_to_match)

rhs = self.evaluate_NFA(curr_state.out2, string_to_match)

return rhs | lhs

elif isinstance(curr_state, Match):

if len(string_to_match) > 0:

return False

else:

return True

The string to match decreases by one element when it matches the Consume state. Note the way Split is handled, we evaluate both the left hand side and the right hand side and return true if either side returns true.

Conclusion

This is not a complete implementation of a regular expression. My objective with this project was to learn how an NFA can be coded and used.